The House of Springside: The Evolution of 'Elmhurst'

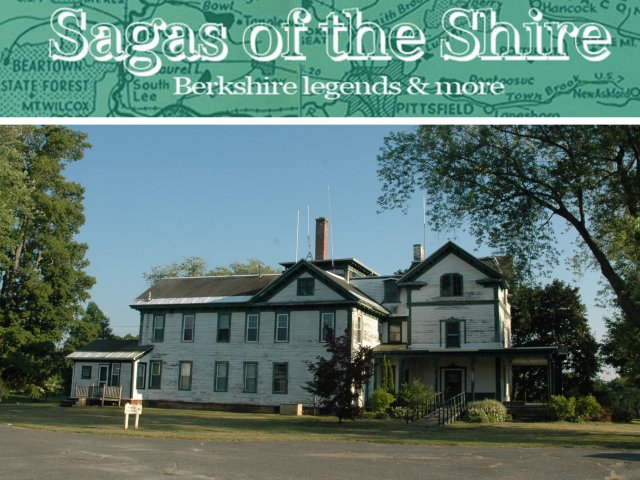

PITTSFIELD, Mass. — There's been a lot of discussion in Pittsfield about the "Springside House" in the last few years, over its possible restoration, and its changing relationship with the history of that city.

One of the most interesting parts of that history that is seldom referenced or fully realized is that the house we mean is not actually the original "Springside" ... that place got torn down over a decade ago.

After Abraham Burbank acquired the Asabel Strong Farm that now makes up a sizable chunk of Springside Park in the early 1850s, he built two significant houses on that property, both of which would serve a variety of roles in local history over the next century and a half.

As it happens, Burbank built quite a few things in the city, and in doing so went from rags to riches over the course of about 50 years.

When he arrived in Pittsfield from West Springfield in 1832 at the age of 19, all he had to his name was 50 cents, an old suit of clothes, and one good shirt wrapped up in a bandanna. He had apprenticed from age 15 to 18 as a carpenter, and early on announced his bold intentions.

A couple of years later, the still struggling newlywed Burbank was refused credit for a bag of flour by one of the most prominent businessmen in town at that time, John C. West, at his general store in West's Block. As the story goes, Burbank is said to have declared to West that he would own in Pittsfield "as many houses as days in the year" and "as many stores as there were weeks." Staying fairly true to his word, Burbank erected numerous downtown blocks, opened up several new streets of houses, and owned multiple hotels, leaving at his death holdings worth $800,000 in 1887.

At Springside, so called for the natural hillside springs there, Burbank in 1856 constructed two houses over the buildings of the former Strong Farm. The first was on the southern part of the parcel, in the vicinity of what would decades later become Abbott Street and Springside Avenue; the second he built farther north, on the crest of the hill, and called it Elmhurst.

Burbank sold the first house and the 30 acres that same year to the Rev. Charles Abbott, who ran the Springside School as a boarding school for boys until after the Civil War, when the boarding school briefly operated as The Pollock Institute. A few years after the school failed, some investors purchased it in 1872, and then resold, expanded and reopened as the Springside Summer Hotel in 1878. It was further enlarged in 1886 so as to offer 30 guest rooms, before being sold to Henry Ryan in 1893 and moved to make way for the development of two new residential streets (Abbott and Springside).

Up the hill, Burbank held onto Elmhurst and its 50 acres until 1872, when he sold it to Brooklyn-based brass manufacturer John Davol. Davol put over twice the purchase price into expansion and alteration, and much of the house's current character dates to his renovations. In addition to changes to the house, Davol also constructed its circular driveway, the barn that currently stands adjacent to it, and the stone entry pillars bearing the name Elmhurst, which can still be seen on North Street just south of the modern entryway to the house and park today.

Davol and later his two sons, Frank and William, used the house as a summer home for decades, until it was sold at auction in 1904 to a friend of the family, Clarence Stephens.

Meanwhile, the original Springside, relocated to the corner of North and Springside Avenue, had been enlarged and re-renovated to reopen as the Elmwood Summer Hotel in 1898. Local attorney George Prediger bought it out and changed it to the Havana Hotel in 1903, though soon after he converted it to apartments.

In 1908, Dr. Charles Harper Richardson, seeing a need for a second Pittsfield hospital devoted to surgery, founded his Hillcrest Hospital in it. It grew and expanded there for the next four decades, before moving to the newly acquired Salisbury family estate Tor Court.

During that period, Stephens had expanded the Elmhurst estate by an additional 75 acres and made several key landscaping changes. Upon his death in 1933, it passed to his son John, who sold it to brothers Donald and Laurence Miller five years later.

The Millers, owners of The Berkshire Eagle, were keen to expand upon the legacy of their father Kelton, a former mayor who in 1910 had donated 10 acres near what was then the end of both Abbott Street and Springside Avenue as "Abbott Park," though everyone proceeded to refer to the park by the traditional name Springside. The Stephens estate was added to the park, and the Parks Commission renamed and reopened the Elmhurst manor as "Springside House" in 1939, immediately becoming a popular venue for parties, dances, and concerts that drew thousands to its sprawling lawn.

For much of World War II, it closed other than for use by the city's Civil Defense department, but reopened again for special events shortly thereafter, until in 1955 it became the new home for the growing Department of Parks & Recreation, its longest occupant to date.

Down the street, the former "Springside" building deteriorated a bit at a time following the relocation of Hillcrest in 1950; it was first used as a nursing home and later as a school for disabled children, until by the end of the 1980s it lay vacant. In 2003, it was demolished.

While it was declining, the new "Springside House" was reaching its peak, headquarters to a growing infrastructure of open spaces and recreational programs, an epicenter of the city's booming athletic and outdoor activity. It would remain as such until a reorganization in 2007 eliminated the department, dividing and absorbing its functions into positions within the Office of Community Development and the Department of Buildings & Maintenance, respectively.

Today, rooms still piled high with stored artifacts from its half century of parks coordination give a glimpse into the diversity of activities that stemmed out from this building. It was a place where city staff developed new park plans and amenities, ordered playground equipment, planned functions, a place to sign up for swimming lessons or soccer league. On the third floor, smaller rooms that had likely once been servants' quarters became designated storage lockers for all manner of local athletic clubs, from Babe Ruth to junior football to speed skating.

Rows of bound minutes on the shelves tell of years of meetings by bodies such as the Parks Commission and the Conservation Commission, while black and white photos show parade preparations and aging, serious-faced men chain-smoking while readying eggs for the annual Easter Egg Hunt.

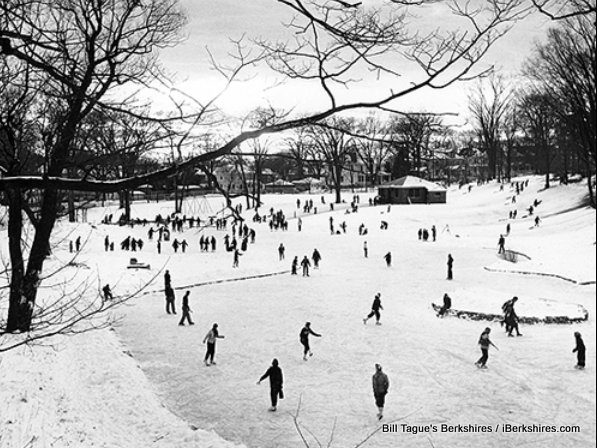

It was a place where for a dollar or so you could rent a pre-packaged "picnic kit," hefty steamer trunks stuffed with softball bats, jump ropes, badminton nets and checker boards; it was the palace in which resided the throne for some 65 consecutive annual Winter Carnival Queens; and the final repository of years of youth championship trophies no one was quite sure what else to do with.

In summer 2013, I had the opportunity to co-curate and docent an exhibit of some of the historic parks and recreation memorabilia that resides in the vacant mansion today. I was taken aback by the number and intensity of memories provoked in visitors, many of whom shared their favorite moments with me. In a small city with a network of around three dozen parks and open spaces, this house on the hill is evocative of decades of community life, including athletic activities, recreational amenities and public gatherings whose attendance dwarfs that of its modern equivalents.

In the 1960s, the scenic campus of park headquarters, maintenance buildings, and elaborate garden spaces seemed a logical choice for the addition of a greenhouse, which has been rented under agreement with the city by a member-based private gardening club ever since. Later, more agricultural and beautification organizations such as Pittsfield Beautiful, the Vincent J. Hebert Athenaeum and Western Massachusetts Master Gardeners Association continued to contribute to the landscaping, gardening, and arboreal improvement of this area of the park.

It is some of these latter activities which have helped to inform the city's recent grant-funded feasibility study, which sought not only to identify the structural needs of its restoration, but gauge public input on an appropriate adaptive reuse of the unique building should be.

According to the final feasibility study, conducted by CME Associates, out of several possible uses, over 70 percent of the public input favored some combination that used the house as a environmental education center and related visitors center, with office spaces devoted to bringing together several conservation, natural education and park stewardship organizations. Devoting space to showcase some of the plentiful local parks history already inhabiting the house was seen as well as holding public events were seen as additional, compatible usages that could further breathe life and purpose into the vacant city owned building.

"The beauty of the variety of spaces within the building allows for multiple uses that very well suits the expressed needs of the community as outlined in the public meetings," reads the feasibility study. "Most of the programs identified could be housed compatibly and naturally within the house without altering the character defining features and historic aspect of the assemblage."

"The model of an integrated Springside Natural Park Center would provide an ideal role for the house as part of a visitor friendly, educational campus area that includes an arboretum, greenhouse facilities, demonstration gardens and hundreds of adjacent acres of diverse ecosystems within Pittsfield's largest park and downtown natural preserve," according to a conceptual proposal endorsed by several independent park and neighborhood organizations.

"By providing a thematic multi-use center that draws upon the existing free resource of multiple organizations already currently engaged in providing a range STEM educational programming at Springside Park, as well as extensive recreational and cultural events held on the grounds," the proposal further states, "Pittsfield can create a facility that will be a unique draw for visitors celebrating the community's proud parks history and modern outdoors tourism offerings while simultaneously providing a tremendous benefit to the community by connecting academic learning with hands on opportunities to study botany, agriculture, forestry, zoology, and numerous other disciplines of naturalist education."

All this is in keeping with a seeming consensus since the building was closed several years ago, that if it is to be restored and reopened, it must serve a sufficiently robust and important purpose to justify the expense of doing so.

Thus, the race to save the house on the hill at Springside has become more than simply a matter of historic preservation. For those who have begun to rally to her cause, it is not merely the love of an old house, not solely limited to the need to retain a structure that is both a staple of historic infrastructure and a prevailing beacon in the psyche of a city struggling to stay afloat between its past and present and salvage some semblance of its image of itself.

Perhaps even more importantly, it is an effort to see these beloved rooms reopened to new purpose, as grand or grander than any they have served before, a striving to take advantage of a unique structural asset within a wild blooming natural asset, an opportunity to galvanize a unique convergence of building and setting for the potential for learning and development it could offer to current and future generations of citizenry.

It is for the latter in particular that some of us who have studied and conferred and lobbied these past several years would see this work undertaken, for the next generation now growing up among us ... a generation that so desperately needs reconnecting to the outdoors; a generation for whom we seek to re-spark a passion for science that has seemed to have temporarily slipped away from America; a generation who will face challenges of environmental stewardship and repair the likes of which have not been the burden of any previous group in the history of humanity.

The writer of this column, Joe Durwin, has recently launched a campaign on Indiegogo.com to fund the publication of a new collection of writings on local folklore and history.

"These Mysterious Hills: An Unauthorized History of the Berkshires" represents the culmination of more than a decade of writing on all things weird in the Berkshires and surrounding area, and covers a wide array of curiosities from three and a half centuries of recorded history in the region.

It will include updated editions of the longtime Advocate Weekly column of the same name, along with material published in Haunted Times, FATE Magazine, iBerkshires.com, the North Adams Transcript and tons of new, never before printed material. By shining a spotlight on the area's more unusual episodes and legends, Durwin believes it will enrich knowledge of local history while attracting new tourist interest in the region.

Check out a video on the project and rewards available to supporters of the book here.

Tags: historic buildings, parks & rec, public parks, sagas of the shire,